'You should’ve seen this 20 years ago' becoming more and more real

Recently, AccuWeather forecasters released their storm predictions for the 2024 Atlantic storm season. They said they expect between 20 and 25 named storms including tropical storms with sustained winds of at least 39 mph. Storms have spun up earlier in recent years, due to warming oceans, but in general the storm season lasts from June 1 to Nov. 30.

They are also calling for four to seven Category 3 or higher hurricanes (at least 111 mph).

For the past 30 years, there have been, on average, 14 named storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Hurricane Center.

Above-average sea-surface temperatures in the Atlantic and particularly in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and throughout the tropics are one cause for this intensification.

“As far as sea surface temperatures go, which is kind of the skin temperature of the ocean, that started breaking records in March last year. And it's been breaking records every day since,” Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, said.

Another concern for the coming storm season is the change in Pacific weather patterns. Hotter waters associated with El Niño are expected to cool with the onset of La Niña. That quick change will reduce disruptive wind shear in the Atlantic, but that change itself could fire up more storms in the Atlantic.

From an article posted by NOAA.

During normal conditions in the Pacific ocean, trade winds blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths — a process called upwelling. El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions. Scientists call these phenomena the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. El Niño and La Niña can both have global impacts on weather, wildfires, ecosystems, and economies. Episodes of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months, but can sometimes last for years. El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years, on average, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule.

La Niña

When things turn around during a La Niña year, cold waters in the Pacific push the jet stream northward. This tends to lead to drought in the southern U.S. and heavy rains and flooding in the Pacific Northwest and Canada. During a La Niña year, winter temperatures are warmer than normal in the South and cooler than normal in the North. La Niña can also lead to a more severe hurricane season.

And that brings us back around to why scientists are concerned about a more severe hurricane season. There is weaker vertical windshear and tradewinds blowing east and less stability in the southern Atlantic. As storms spin up, there is nothing to break them up.

Coral Bleaching

From the same WUSF article:

Dalton Hesley, a senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School, witnessed the coral bleaching in action. Hesley works at Dr. Diego Lirman's Benthic Ecology and Coral Reef Restoration Lab at the school.

“Months prior to when we would typically expect something like that, we had the Florida Keys sounding the alarm, where they were seeing mass bleaching and entire coral nurseries lost. And we didn't think that was possible,” Hesley said on The Florida Roundup.

“We had to act very quickly and launch capacity resources, team members to try to essentially move as many corals as possible from offshore, potentially in harm's way on to these land-based nurseries and resources.”

La Niña and El Niño have been happening for hundreds of years that we know of, but combined with the warming ocean temperatures, they seem to be oscillating more frequently and causing more extreme problems in the Atlantic and the Pacific as well as across the United States. I live in an inland, land-locked state, but still the changing jet streams have significantly altered the winter weather conditions where I live. Winter used to last through most of March, but now, by the end of February we are already seeing the first flowers of spring.

It is also leading to tornadoes in places where they rarely happened before, flooding and wildfires from the dry air and exceptional winds.

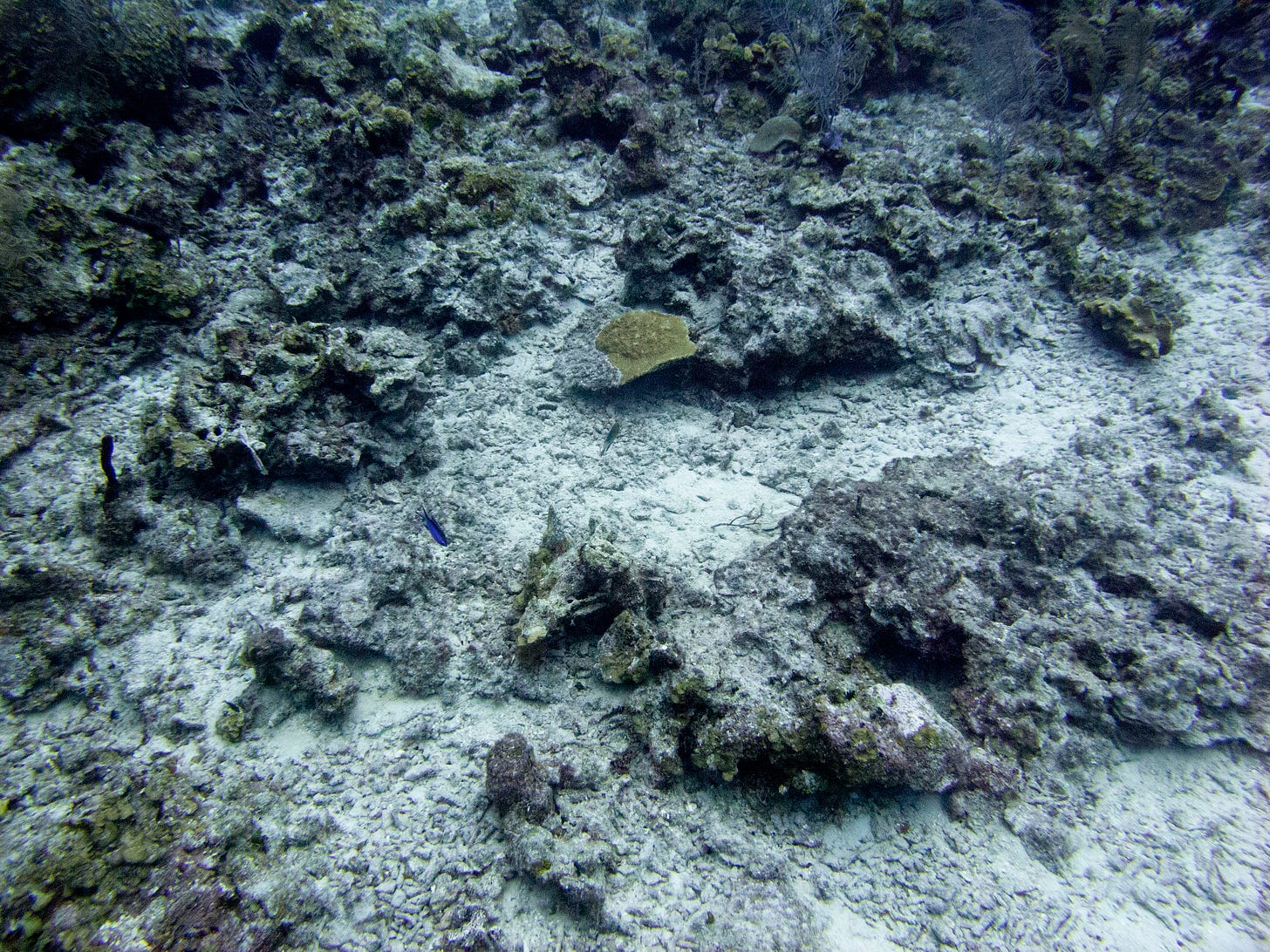

The record heat in the ocean has caused significant coral bleaching events as well. That’s when the symbiotic organisms inside corals die off from the heat. They can recover when the temperatures return to normal, but when a storm comes through while they are in their weakened state, coral reefs can turn into fields of rubble. And then that reef is less able to protect the coastline from storm damage like storm surge later.

As a diver, I’ve seen coral reefs that look like a bulldozer plowed over them. I’ve also seen the valiant efforts of scientists trying to restore those same reefs. I always used to laugh at “old-timers” and the standard phrase “You should’ve seen this 20 years ago.”

Unfortunately, now that I am one of those old-timers, I am beginning to see what they mean. The oceans don’t look like they did 30 years ago when I made my first ocean dives. And I’m sure they didn’t look then like they did 30 years before that.

I’m keeping this Substack free for now, but if you’d like to support it anyway, buy me a cup of Kofi.

I also recommend you follow me on my Facebook Author Page, Instagram and Threads.