Last week, in my essay about wreck diving (and owning your own shipwreck) I mentioned a side story that came up after I published my novel Wreck of the Huron: Cuban Secrets.

Steve Lovell, a British diver, searched the web for notable burials in an old cemetery where he lived and that’s when he stumbled on the story of what is likely one of the most unusual Medal of Honor recipients in U.S. history. And was tied to my novel so he reached out to me.

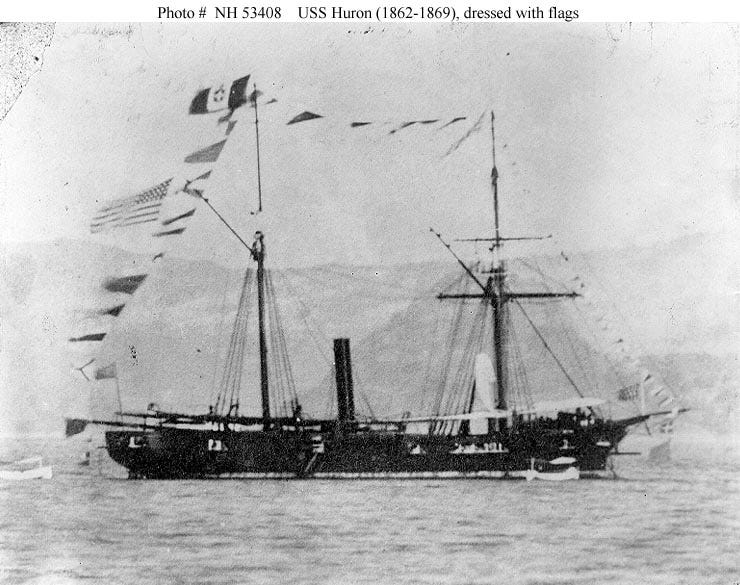

The USS Huron is a real shipwreck located just a few hundred yards off shore in Nags Head, North Carolina. Most of the novel is set in the present day, but there are several scenes that are set in 1877 on board the ship on the day it sank.

The ship and her crew were headed to Cuba to perform environmental surveys and ran aground. Of 132 crew and officers on board, 98 drowned. They were only about 200 yards from the beach, but the US Lifesaving Service was not at that time functioning year-round and there was no one there to help. That wreck of the Huron and another shipwreck several months later prompted congress to fund the lifesaving service 12 months out of the year.

To tell that story and to make it as realistic as possible, I used quotes and the names and accounts from the men who survived the wreck. Those accounts were recorded in the Proceedings of Court of Inquiry on the Loss of the Huron held by the Navy Department, Washington DC, Wednesday, December 5, 1877. The wreck happened in the early morning hours on November 24, 1877.

Here is an excerpt for the account of the accident just as the ship ran aground, as retold in Wreck of the Huron:

With each wave that passed, the jarring of the hull against the bottom was lessened — only because the ship was run further aground and was lifted less and less.

“Stop the engines!” Ryan ordered from the bridge. “Palmer, find out if we still have steam in the boilers. I want to see if we can back her out of here before the hull gets holed.”

Master French pulled back on the throttle, signaling the engineer to stop the engines. Palmer left his station to yell down the hatch to the engine room below.

“Can you back her, engineer?” Palmer asked.

“We’ve got full steam on all the engines. Yes, we can,” Chief Engineer Loomis replied.

“Make it happen, Mr. Loomis,” Palmer ordered.

“Mr. French, save the ship’s log. We’ve probably foundered on Nags Head. Mr. Palmer, please sound the distress whistle. We’re going to need some help,” Ryan said, taking charge of the bridge. “Get all hands on deck and batten down the hatches. Get those sails lowered.”

Within moments, French reported back to the bridge that the captain’s office where the ship’s log was stored was filled with water, being on the starboard side.

“Very well,” Ryan acknowledged. “Lieutenant Simons, order the fore mast cut away, please. Maybe we can right this ship without the added weight.”

“I will make it happen immediately,” Simons said, leaving across the angled deck to organize the men. The Huron was over on her side, at about 40 degrees.

In one scene, I followed William P. Conway, the watch commander, as he swam ashore and then helped rescue some of the other men who survived the wreck. What I didn’t know about were the actions of Antonio Williams. He was also on the ship and was side-by-side with Conway coming ashore. Williams wasn’t mentioned specifically in the inquest and he wasn’t interviewed because he was still in the hospital recovering from his injuries.

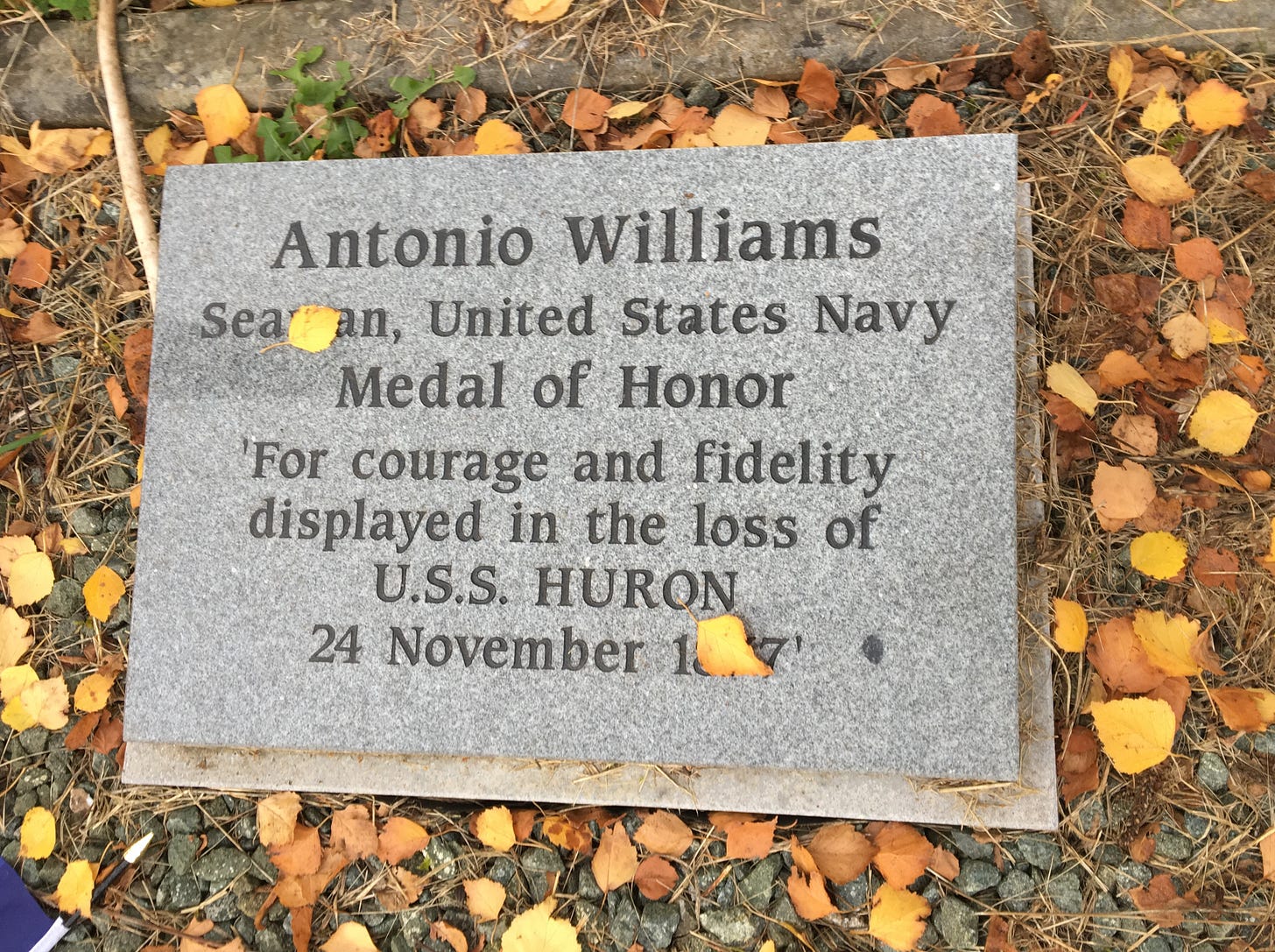

Antonio Williams received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions that day making him the oldest recipient of the award — he was 51 at the time. (Until just before World War II, servicemen could receive the award in peacetime. Now it is only given for actions during war.)

Williams was born in Malta in 1830 and came to the United States in 1867, after being shanghaied and serving aboard a whaler in his youth. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1890—the same year he retired from the Navy. He later moved to England, his wife’s home.

The Secretary of the Navy, in sending the medal to Antonio Williams, wrote “It is shown in evidence that upon that occasion, the wrecking of the U.S.N. steamer Huron, you gave up whatever chance of life a foothold upon the wrecked vessel offered by taking to the sea, with Ensign Young, on a small balsa in the attempt to carry a line to the shore for the relief of your ship-mates. The effort failed by the shortness of the line. Four times capsized on the balsa, and nearly drowned, you reached the shore, where, before you were clear of the undertow, and notwithstanding your bruises and worn condition, joining hands with your companion, you helped with him to haul two men out of the water, and afterward, joining hands with him again, and running back into the surf, hauled out two more. It is also shown that you rendered material assistance to the weak and exhausted men whom you had saved.”

In an interview with Harper's Weekly he was asked “Did you think you would reach the shore?”

“Yes, I did; and every time the sea knocked me off the balsa I set my teeth the harder together, and made up my mind to do my best. The sea off that coast of North Carolina would take me and throw me clear off of the balsa and then I would have to get back again. I was very much battered and bruised, as was Mr. Young, but he was as brave as you ever find them. If we had only known that we were 300 yards from the shore we might have done better, but we could not see. It was pitch dark. I said to myself the wind and the sea must fetch us up somewhere near the shore, and we worked about three miles of a course on that balsa before we struck the beach, and we struck it hard, I tell you. Of course I must have been used up, but I didn’t know it then… I saw more work to do, and I forgot the pains in my back, where the seas, or a spar, or something struck me. I was three months in hospital before I got all over it. I never was a strong man after it; though my nerves were just as good as ever…”

Later in his career, Williams was at sea on the Corvette Yantic and faced another severe storm. Harper's Weekly wrote: when it was thought that the Yantic would founder, (Williams ) strapped on his medals, and declared that if he went down he would still carry his decorations for manly and honorable conduct about him. “That’s the belt I put them in, and I wear it for three days-until the medals hurt my back. The sea make the bronze medal a little green, but the gold one is just as bright as when my adopted country give it me.”

Williams was buried at Greenbank Cemetery in Bristol, England with honors. The minister who officiated said he was struck by Williams’ idea of Christianity and his preparations for the afterlife. Being a man who obeyed orders all of his life, Williams said “when the order came from his Captain to go aloft, he would be ready to obey.”

Lovell noted that he visited Williams’ cemetery plot and it was run down and very plain. He cleaned it up and placed a cross of remembrance on it.

And then made it a personal project to obtain a headstone for Williams’ grave and to give the man the honor he deserved. He met with various cemetery officials and a stone mason to make the arrangements.

Working with the Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation, Lovell got a new headstone placed on the grave and on Monday, June 23, 2014 Lovell assembled a group to rededicate Williams’ grave. In attendance were:

Tony Walworth from the Royal Naval Association who sounded the Bosuns Call.

Rev. Angie Hoare from Eastville Park Methodist Church who performed a reading and prayers. Eastville Park Methodist is the church Williams attended.

Capt. David Stracener, the U.S. Naval attaché in London, who unveiled the new headstone.

The BBC published this story on the rededication.

I’m keeping this Substack free for now, but if you’d like to support it anyway, buy me a cup of Kofi.

Check out my fiction at BooksbyEric.com.

I also recommend you follow me on my Facebook Author Page, Instagram and Threads.