Protect what we love or, maybe, what we fear losing

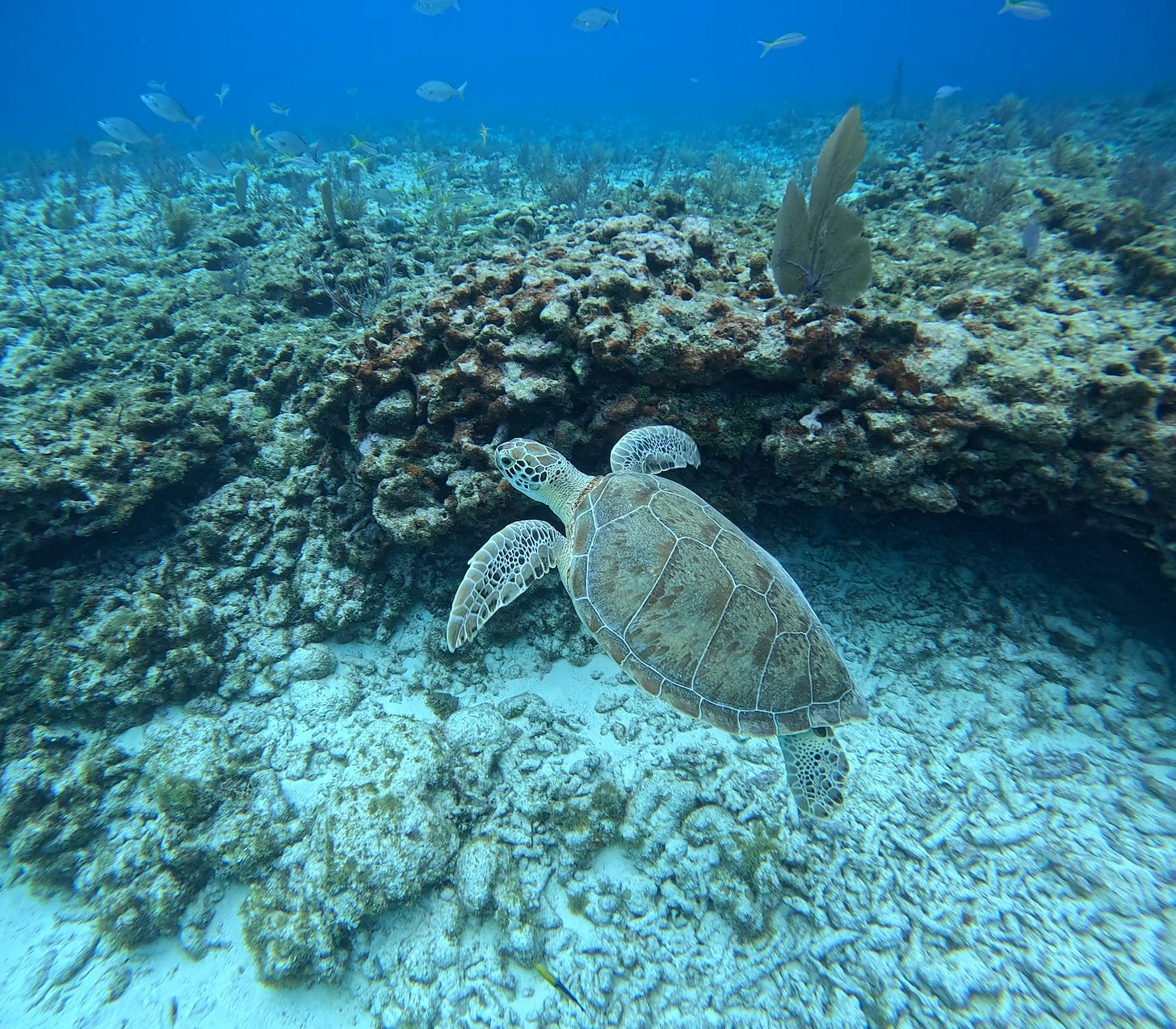

Floating underwater in the Keys last week had me thinking about the ocean and what we can do to protect it. I got great responses to the photos I shared and one friend told me he was living vicariously through them since he was working.

Of course, that made me feel good, but I doubt it moved the needle all that much.

I’ve used my novels in much the same way. I hope to expose my readers to the wonders of the ocean, the mysteries of shipwrecks and the excitement of diving.

But I realize I am a relatively small voice in the crowd of ocean writers — and especially when we come up against government and industry that profits from the oceans. That’s why I was intrigued to read an essay from Alexandra Cousteau recently.

On more than one occasion I’ve quoted her grandfather Jacques as saying:

“We only protect what we love, we only love what we understand, and we only understand what we are taught.”

Alexandra recently wrote about the recent UN Ocean Conference in the essay Empty Promises in Nice: France’s Ocean Hypocrisy on Full Display:

“France could have chosen to actually protect its coastal waters, support small-scale fishers, strengthen local ports, and invest in coastal resilience. A ban on industrial trawling in MPAs would have done exactly that. MPAs, when properly enforced, are known to be fountains of life. But no—too disruptive. Some industrial fleets might be inconvenienced. Never mind that many of those fleets aren’t even French. Never mind that the EU has funds specifically to help support transitions away from harmful practices.

And then she noted the irony of French President Emmanual Macron’s position.

But the best line came from Macron himself. On national television, he declared that he “didn’t need lessons in ecology.” (Apparently, he’s got it all covered.) Then, on a talk show, he added: “Without bottom trawling, we won’t have any more scallops.” Yes. That’s the hill we’re dying on. Scallops.

This isn’t leadership. This is parody.

She quoted a report from Oceana, the ocean advocacy and environmental organization.

Their analysis found that more than 100 bottom trawlers spent over 17,000 hours fishing inside France’s six marine national parks in European waters in 2024. Yes, in the “protected” ones. That’s the equivalent of one boat fishing around the clock for nearly two years straight. Apparently in France, “protection” just means adding a fancy label and hoping no one looks too closely. (Read Report)

Semi-related, but I worked with Oceana about 15 years ago when they published my children’s book called Sea Turtle Rescue as a giveaway.

The entire essay really is worth a read. Forbes also did a story on it.

One of the biggest issues she discussed was bottom trawling. This is a hot topic right now since Sir David Attenborough’s latest film came out with the first cinema quality view of what happens when a huge, weighted net is dragged across the ocean bottom.

I actually used this issue in a short story I wrote a decade ago called Queen Conch. Watching the video makes me realize I didn’t make it out to be nearly destructive enough.

Back to the Jacques Cousteau quote, an interesting study came out recently, quantifying that assertion. I read about it in an article in Phys.org called Research shows how emotional responses are motivating divers to help restore the Great Barrier Reef. Here’s an excerpt:

Dr. Ella Vallelonga, from the University of Adelaide's Department of Anthropology and Development Studies, examined how reef conservation diving dissolves "human exceptionalism"—the idea that humans are separate from, or superior to, other animals—and builds deep interspecies connections.

Vallelonga's research focused on scuba diving-based reef restoration. She was surprised to find that the sensory components of marine submersion, from the feeling of water pressure to the tactile nature of coral care, prompted powerful emotions corresponding with empathy and protection.

Published in Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology, the study involved 13 months of ethnographic research in Far North Queensland between 2022 and 2023. Dr. Vallelonga used participant observation and semi-structured interviews with coastal stewards, reef advocates, rainforest restorationists, marine scientists and reef recovery divers.

I certainly don’t know the best way to motivate the public (and our governments and industry) to protect the ocean. I agree with Jacques Cousteau about finding ways for people to understand so they love it. But it seems scientifically the fear of losing it may be a more powerful motivator.

I’m keeping this Substack free for now, but if you’d like to support it anyway, buy me a cup of Kofi.

Check out my fiction at BooksbyEric.com.

I also recommend you follow me on my Facebook Author Page, Instagram and Threads.